Health Care & Wellness

State Abortion Legislation Tackled Medication Access in 2025

January 23, 2026 | Mary Kate Barnauskas

September 27, 2024 | Megan Barton, Brock Ingmire

Key Takeaways:

This MultiState Insider is coauthored by a guest author, Megan Barton, Chief Clinical Officer at Community CareLink. Community CareLink was established to address the critical need for enhanced support for individuals facing systemic, community-level issues. Dedicated to improving the lives of individuals and communities through its comprehensive, first of its kind platform, Community CareLink seamlessly integrates social and healthcare services to drive outcomes. Contact: mbarton@communitycarelink.com.

Research has consistently shown that access to nutritious foods, reliable transportation and affordable housing can significantly improve an individual’s physical and mental health. Despite this, federal law has historically limited the ability of states to spend Medicaid dollars for such uses. Access to food, transportation and housing, and similarly situated needs, are typically referred to as either social determinants of health or health-related social needs (HRSNs). As the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has defined, “HRSNs are social and economic needs that individuals experience that affect their ability to maintain their health and well-being.”

Recently, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the regulator in charge of how states may spend their Medicaid dollars and an agency housed at HHS, has been more willing to allow for states to reimburse medical and social service providers for services that address HRSNs. In November 2023, HHS issued a Call to Action encouraging Medicaid stakeholders to address unmet HRSNs for Medicaid members. This came after two years of work by CMS, state Medicaid agencies, and stakeholders to identify and redefine existing pathways in federal laws that would authorize certain HRSN services as reimbursable for wide-scale use.

In 2021, CMS identified opportunities for states to address HRSNs through 1915 waivers and state plan options, with the intent to help with the daily activities of living for those who were aged and disabled. Later that year, CMS’s approval of California’s plan to utilize In Lieu of Service and Settings (ILOS) authority provided yet another systemic pathway for states to invest in HRSNs for more than just a targeted audience. Since 2016, the ILOS pathway allows Medicaid managed care plans to pay for nonmedical services instead of standard Medicaid benefits, if it is medically appropriate and cost-effective to do so. CMS expanded that authority with their approval in California, by allowing an ILOS to be (1) preventative of a future service and (2) not needing to be a direct substitute for an existing service. For instance, in California, nutritious meals and asthma remediation were approved as an ILOS recognizing it may prevent future, more costly use of other Medicaid services. While 2023 guidance limited expenditures for ILOSs at 5 percent of total capitation payments for managed care organizations, it created a sustainable financing pathway to scale benefits addressing HRSNs.

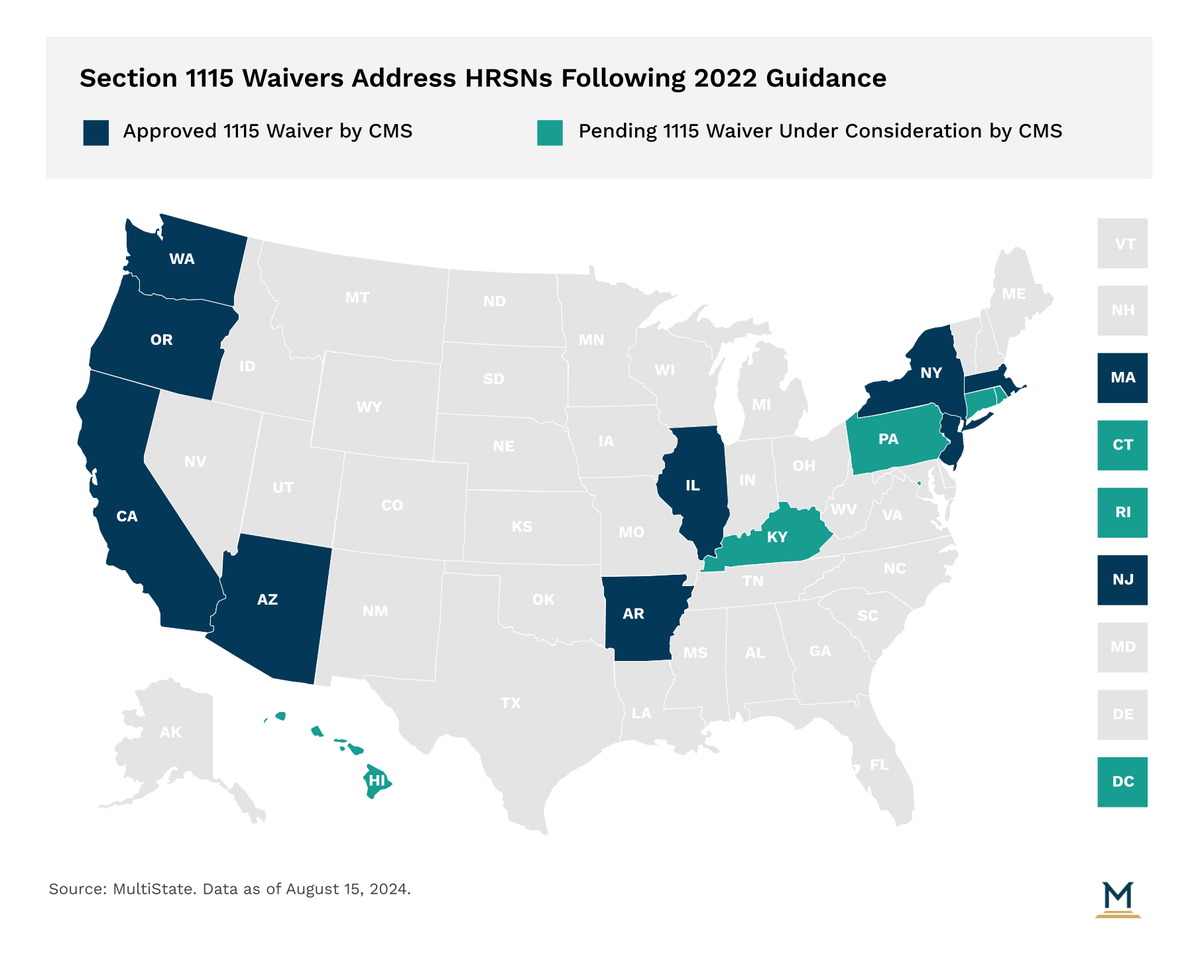

The big shift occurred following approval of section 1115 demonstrations from Arizona, Arkansas, Massachusetts and Oregon in 2022, CMS established an additional and more expansive framework for how states may utilize federal dollars to address HRSN to scale across Medicaid. This framework was:

States may expend federal dollars on HRSN expenditures but are limited on such spending of federal dollars at 3 percent of a state’s total Medicaid spend.

States must meet provider payment rate standards, including increased rates for primary care, behavioral health and obstetrics services that are currently less than 80 percent of Medicare.

HRSN covered services and investments must result in complementary new services and may not supplant an existing program.

In 2024, states began to drive implementation of ILOS and 1115 demonstration authority of HRSN benefits. In doing so, continuous questions arose as to whether there existed provider capacity to accommodate this influx of new, reimbursable HRSN services and who these providers may be that would be able to render such services. Some services fall into categories that providers are currently doing and have not previously been reimbursed for. Other services will incorporate community-based agencies who have not previously interacted with Medicaid programs and benefits. Agencies who supply community services such as housing, nutrition, and criminal justice will now be eligible for Medicaid reimbursement.

While it may sound simple on the surface, integrating community services into the Medicaid benefit is very complex from a state, managed care, and community agency perspective. States must determine participation and provider registration requirements, choose which billing codes to use, set a fee-schedule, set-up their systems to be able to ingest the codes through encounters, create reporting/data requirements and templates, and facilitate any necessary committees and feedback loops.

Managed Care Organizations are playing an active role in defining the requirements and reporting, creating payment structures, contracting with community agencies, and supporting the agencies with implementation. Despite this heightened engagement, many community agencies are still stepping into a new world. They will need to ensure they meet the participation requirements, contract with Managed Care, incorporate a new funding structure, and establish insurance verification and billing/claims submission processes.

In addition to the coordination needed for these new providers entering the Medicaid space, coordination between state agencies that render HRSN-like benefits remains a necessity. How Medicaid agencies partner with other state agencies to create complementary systems that reduce pressure from each other, create efficiencies in financing, and eliminate the agency silos to render services is a monumental task for states. Arguably the key considerations that states will have to grapple with during implementation of HRSN covered benefits are:

Ensuring referral networks aren’t just tied in between members, health and social service provider, but also state agencies beyond Medicaid.

Establishing data-sharing agreements between agencies that ensure a holistic approach is utilized to target Medicaid investments to address HRSNs.

Establishing an intra-agency or cross-agency team that serves to build spaces for state stakeholders to collaborate on how best to maximize investment and target areas of need relative to HRSN covered benefits.

Addressing HRSNs is intended to improve Medicaid members’ health outcomes and drive efficiencies in Medicaid. However, the ability to do so doesn’t remain without administrative hurdles. For instance, regardless of the regulatory authority leveraged to implement HRSN covered benefits, the amount a state is authorized to spend still remains capped. In the original guidance for 1115 authority, of the total 3 percent of the Medicaid budget that may be proportionally spent on HRSN benefits, only 15 percent of that is authorized for HRSN infrastructure investment. For states that have a high Medicaid population, a lower federal matching assistance percentage, yet have a desire to scale HRSN benefits, the state may need to invest their own dollars to build out this social services capacity and the required implementation resources.

When Medicaid programs and stakeholders feel as if they can navigate the financing, administrative and workforce hurdles that may exist, the key aspect of successfully implementing HRSN benefits is to keep the overarching goal of improving healthcare quality and costs at the forefront. All of the necessary collaborations and complexities can make it challenging to remain focused on the intended results. Stakeholders will need to make it as easy as possible to do the right thing, implement processes that allow for tracking of outcomes, use technology that has interoperability capabilities, and leverage the strengths and partnership from the individual entities to create a coordinated effort.

As part of this new framework, CMS also adopted changes to its budget neutrality policy. Long standing CMS policy of 1115 demonstrations is that they must be strictly budget neutral for the federal government. Now, CMS authorized budget neutrality to expand by: authorizing HRSN investment to not require any offset savings, expand the limit on savings realized from 1115 demonstrations that may be carried over to new demonstration periods, an allowance for states to adjust spending projections during the demonstration, and a reliance on more generous trend rates for spending projections. This broader budget neutrality policy is likely what has enabled states to pursue a larger eligible population for HRSN-related services.

The ever-evolving state health policy landscape will continue to influence how health care organizations make business decisions. MultiState’s team pulls from decades of expertise to help you effectively navigate and engage. MultiState’s team understands the issues, knows the key players and organizations, and we harness that expertise to help our clients effectively navigate and engage on their policy priorities. We offer customized strategic solutions to help you develop and execute a proactive multistate agenda focused on your company’s goals. Contact us to learn more about our Health Care Policy Practice.

January 23, 2026 | Mary Kate Barnauskas

January 16, 2026 | Bill Kramer

January 14, 2026 | Katherine Tschopp