Technology & Privacy, Tax & Budgets, Health Care & Wellness

ICYMI: Major Emerging Legislative Trends in 2025 (Webinar Recap)

April 8, 2025 | Liz Malm

February 4, 2025 | Max Rieper, Kim Miller, Sarah Doyle

Key Takeaways:

At the end of each year, our policy analysts share insights on the issues that have been at the forefront of state legislatures throughout the session during their review of thousands of bills across all 50 states. Here are the big developments and high-level trends we saw last year in the technology and privacy space, plus what you can expect in 2025.

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology has been around for years in some fashion. But the emergence of generative AI tools such as ChatGPT and Midjourney that are able to create text and visual images has captured people’s imagination and terrified others with worries of robots taking over the world. While some of the doomsday scenarios seem far-fetched, there are more immediate and realistic concerns with the use of AI technology such as algorithmic bias and discrimination, deepfakes that mislead the public and are used for nefarious means, and incorrect outputs produced by untrustworthy models.

While the White House has issued a framework for an AI Bill of Rights, the federal government has been slow to act to address any of these concerns. State lawmakers have attempted to take the lead, with several forming a multi-state, bipartisan study group on the topic. Over 600 bills in 45 states were introduced on the topic in 2024, although most bills were narrow in scope.

Only a few states made attempts at a comprehensive regulatory approach to AI models. Colorado lawmakers passed the first law that would “establish foundational guardrails for developers utilizing high-risk AI systems,” according to bill sponsor Sen. Robert Rodriguez (D). The law is limited to just those “high-risk” systems that make “consequential decisions” of significant effect, requiring model developers and deployers reasonable care to protect consumers from any known or “reasonably foreseeable” risks of algorithmic discrimination. Consumers must be notified that AI is being used to make consequential decisions and be given the ability to appeal adverse decisions for human review. The law is not set to go into effect until 2026, and lawmakers have already signaled the need to tweak the measure to address industry concerns.

Utah passed a significant AI law, although it was more narrow in scope than Colorado. The measure requires disclosures from certain industries regarding AI use in interactions with consumers. In addition to regulation, the law creates a Learning Laboratory Program that studies the risks, benefits, and impacts of AI and provides a regulatory sandbox for registered participants to experiment with the technology without burdensome regulatory oversight.

Many industry observers anticipated California and Connecticut being the first to pass AI legislation, but efforts at major regulatory bills in those states fell short due to a lack of gubernatorial support. In Connecticut, Sen. James Maroney (D) had chaired a study committee on AI for a year, culminating in a large omnibus AI bill that would have imposed obligations on developers and deployers of AI systems, requiring “reasonable care” to protect against algorithmic discrimination. But despite easily passing the Senate, it never had the support of Gov. Ned Lamont (D), who threatened a veto over concerns the bill would make the state an outlier and hostile to the AI industry.

California lawmakers were able to push through a comprehensive AI regulation bill only to have it vetoed by Gov. Gavin Newsom (D). The proposed measure would have required developers to register their models with a state agency and comply with regulations to mitigate the risk of critical harm to consumers. Newsom vetoed the measure arguing it could create a “false sense of security” by omitting smaller specialized models, an argument at odds with his previous warnings to avoid over-regulating the industry.

Newsom did sign several other AI bills into law including measures to require disclosure by generative AI developers on the data used to train systems, requirements to make AI detection tools available to users, disclosures by health care providers to patients on AI use, protections for artists against “digital replicas,” and other provisions on sexual and political deepfakes.

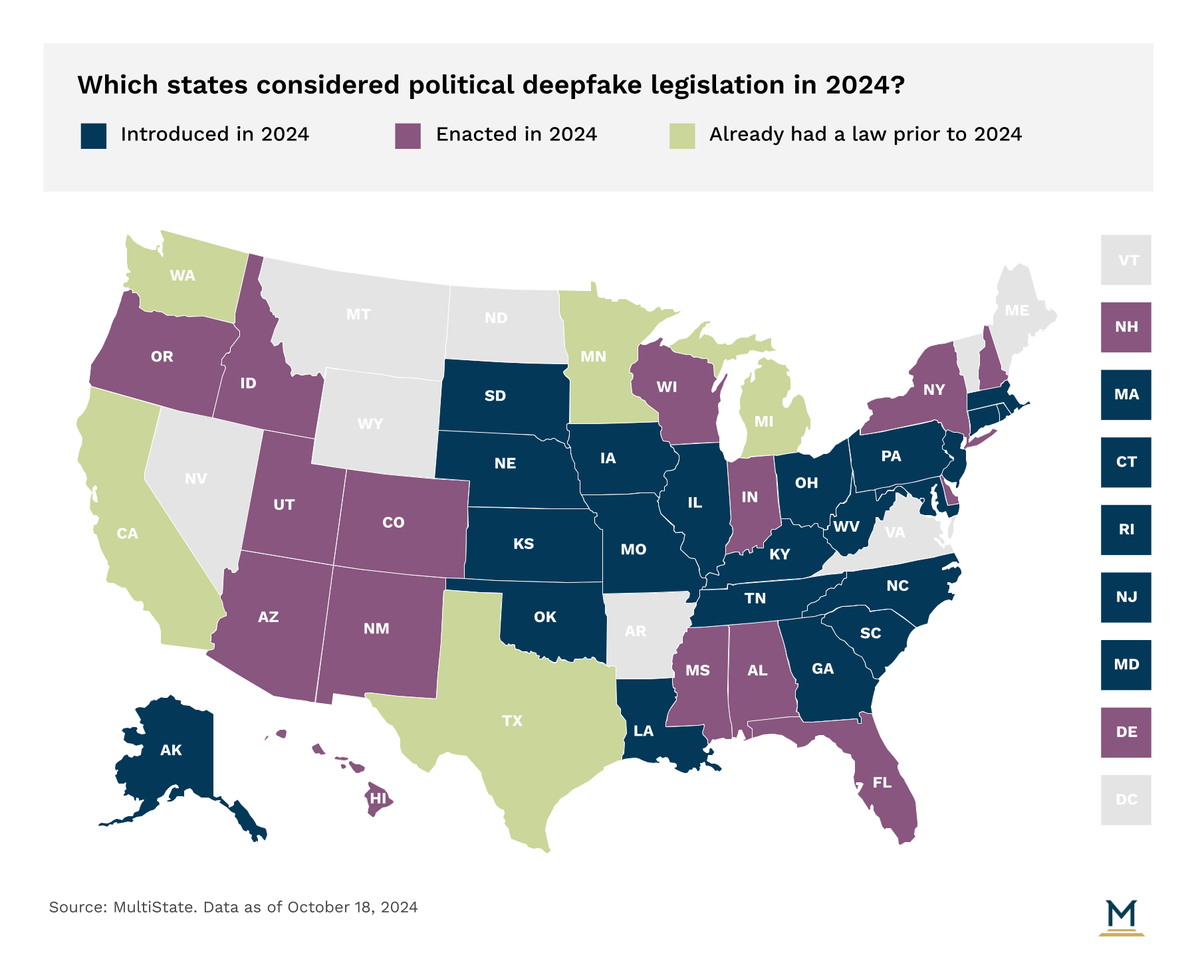

Deepfakes were a concern for many states, with lawmakers considering over 300 bills relating to digitally-created content. Many strengthened child sexual abuse material or nonconsensual “revenge porn” statutes to include digitally-created content. Others required that political communications near an election that were created or altered by AI run with a disclaimer to viewers.

Many states have created study committees on AI that will be producing reports or legislative recommendations for 2025. Expect more states to take action on deepfakes, particularly if there are any impactful AI-generated political ads this fall. Lawmakers will also look at developing guidelines for AI use by state government, and ways to increase efficiency by harnessing the technology. California lawmakers are likely to return with another attempt at a comprehensive regulatory AI law that addresses Newsom’s concerns. Maroney has already said he will come back with a better AI bill next session in Connecticut. Texas Rep.Giovanni Capriglione (R) has worked with Maroney on the multi-state study group and is planning to introduce a comprehensive bill next session, although with perhaps a more business-friendly approach. New York lawmakers are planning legislation for next session to develop a regulatory framework and combat deepfakes.

Newer issues could gain steam next session, such as concerns about rent-setting algorithms, hiring and employment algorithms, consumer protections for AI-generated content, and the use of deepfakes for fraud. The technology is so new that lawmakers are still trying to catch up and understand the benefits and harms it poses. This is certainly just the first step in a long process to set guardrails for a revolutionary technology.

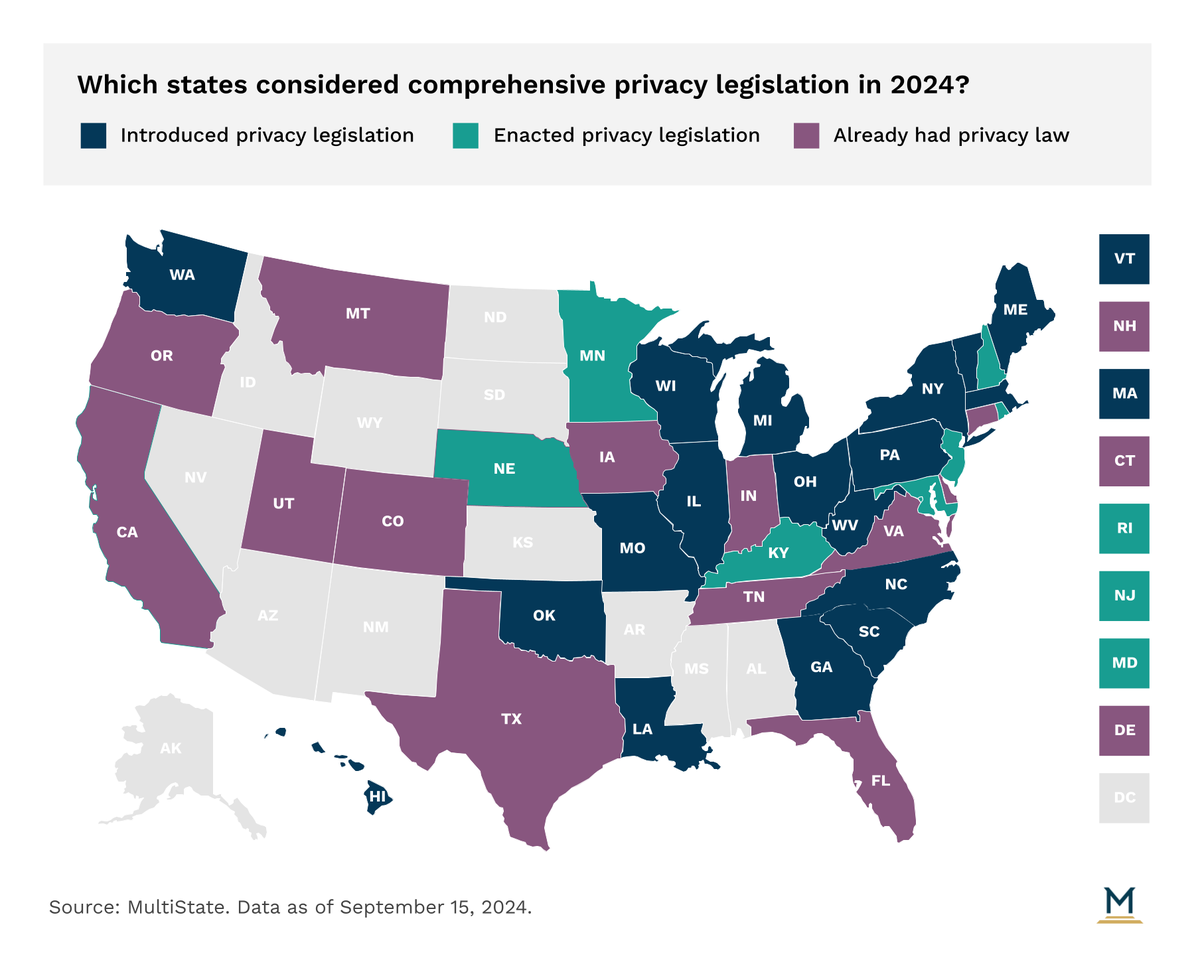

Since California passed its landmark comprehensive data privacy law in 2018, there has been a steady march of states that have followed with their own rules on how companies can use the data collected from consumers. 2024 marked a tipping point as seven more states enacted privacy legislation, bringing the number with a privacy law on the books to 20. Over half the U.S. population is now covered by varying data privacy laws.

Kentucky (KY HB 15), Maryland (MD HB 567/SB 541), Minnesota (MN HF 4757), Nebraska (NE LB 1074), New Hampshire (NH SB 255), New Jersey (NJ SB 332), and Rhode Island (RI SB 2500) all enacted comprehensive privacy laws that largely mirror the standard set by other states where consumers are given certain rights over data collected from them by businesses, including rights to obtain a portable copy of the data, to correct inaccuracies, to have data deleted, and to opt out of processes like targeted advertising, profiling, or having the data sold to a third party.

The Vermont Legislature passed a privacy bill as well, but it was vetoed by Governor Phil Scott (R) who feared the law would make the state an outlier since it would be the first to allow consumers to have a private right of action to sue for violations.

Vermont was not the only state to consider a private right of action – a Maine bill originally included a similar provision and would have had the strictest data minimization regulations in the country before it stalled out in the legislature. In 2024, state lawmakers in general pushed for more consumer-friendly measures in privacy legislation For example, Maryland’s new law severely restricts how data can be used and prohibits all targeted advertising for minors without giving them a chance to consent. More states are trying to make it easier for consumers to exercise rights by requiring companies to recognize universal opt-out signals such as browser extensions.

In addition to activity on comprehensive data privacy laws, Illinois also amended its landmark biometric law to clarify that each separate instance of capturing biometric data from the same individual does not constitute a separate new violation as a court held. Colorado added its own biometric law to protect employees as well as a novel bill to protect “neural data” from brain activity that could be collected from new technology like electroencephalogram headbands and implantable computer chips. California passed a similar law before adjourning in 2024.

There was also a huge spike in legislative activity meant to protect children online. Maryland lawmakers passed a Kids Code that requires data protection impact assessments to determine which online services could pose a harm to children and restricts the use and collection of certain information from minors, such as geolocation data. Lawmakers crafted the legislation in an attempt to avoid an injunction that held up a similar “Age-Appropriate Design” law in California.

State lawmakers also sought to keep minors from accessing adult content through laws that require age verification for certain online content. But many of the laws have been held up by courts on First Amendment free speech grounds, and the Supreme Court has agreed to take up a case this term challenging a Texas law.

The decision in that case could guide and embolden other states to take aggressive action to protect children online. Having already targeted online websites, lawmakers could turn next to requiring devices to have content filters, like a new law in Utah that passed in 2024, or even requiring app stores to restrict certain apps from minors. Many states have also tried to pass laws to restrict addictive features on social media for minors or require parental consent to obtain an account.

On privacy, lawmakers are pushing for more consumer-friendly measures, with some advocates insisting upon a private right of action to enforce laws. Some lawmakers want to make it easier for consumers to opt out of certain practices and could require recognition of universal opt-out mechanisms like browser extensions to signal an opt-out. California’s DELETE Act could serve as a model for other states to make it easy for consumers to have data held by businesses to be deleted with one press of a button.

Data centers will likely become of increasing interest to states in 2025 and beyond. Finding a suitable location for data centers at one point may have primarily involved finding a suitable location for a warehouse to store rows and rows of servers. However, today constructing a data center raises several questions concerning energy availability and water usage. Furthermore, areas such as Northern Virginia are currently grappling with the consequences of having a very high concentration of data centers in one area, with residents raising concerns about the large, warehouse-like buildings bringing noise and pollution backup generators.

Data centers, already essential for storing and processing data from traditional online applications, will become more important as artificial intelligence programs expand and become more integrated into everyday lives. However, the data centers used to process all this information use extraordinary amounts of water and energy. One data center can consume up to 50 times as much energy as a typical commercial office building. Data centers also use a large amount of water to cool data servers with medium-sized data centers consuming up to 300,000 gallons of water a day. The amount of water used by data centers can be especially problematic in areas that are prone to drought as water restrictions could potentially negatively impact data center operations. However, despite the incredible energy and water usage demands of data centers, 36 states offer some form of tax incentive for data center operators.

Data center legislation in 2024 was not a nationwide trend. However, there were notable developments in Virginia, Maryland, Georgia, and Texas that are worth noting as they may be an indicator for future data center discussions in other states seeking to attract data center operators.

Virginia is currently home to more than 300 data centers, the vast majority of which are located in the northern part of the state. These data centers, while welcomed at first, have become an increasing source of frustration for local residents. These frustrations, long-standing agenda items at the local level, are now causing state lawmakers to act. In 2024, Virginia lawmakers introduced legislation aimed at limiting data center construction by prohibiting data centers from being constructed in certain areas, establishing new provisions for how data centers use and reuse water, requiring certain transmission lines to be buried, and allowing local governments to perform site assessments to determine the impact a data center may have on the community. While none of these bills made it across the finish line, several have been slated to be reintroduced in 2025, including a part of a package of bills (VA SB 284, VA SB 285, and VA SB 289) introduced by Senator Danica Roem (D).

In neighboring Maryland, data centers are also front of mind for many state lawmakers. In 2024, Governor Wes Moore (D) signed the Critical Infrastructure Streamlining Act (MD SB 474/HB 579) into law which amends the definition of backup generators and changes when approval is needed from the Maryland Public Service Commission to install backup generators. This legislation was enacted after the Maryland Public Service Commission denied a request to install 168 diesel backup generators in January on a data center campus that was being planned in Frederick County. This legislation passed the legislature unanimously, signaling strong bipartisan support for data centers in Maryland. When signing the legislation, Governor Moore stated, “This bill is going to supercharge the data center industry in Maryland, so we can unleash more economic potential and create more good paying union jobs.”

In Georgia, data centers have begun to attract negative attention from state and local lawmakers. During the 2024 legislative session, the Georgia legislature passed legislation (GA HB 1192), which would have suspended the state’s tax exemption for data centers from July 1, 2024, until June 30, 2026. However, Governor Brian Kemp (R) vetoed this bill, stating that the legislation would have undermined investments that had already been made into data center construction in the state. At the local level, the Atlanta City Council recently passed an ordinance prohibiting data center construction near transit stops and areas near a planned trail, transportation, and economic development project that local officials would prefer to be used for housing, retail, and green spaces.

The Texas Legislature was not in regular session in 2024, but that did not prevent lawmakers from beginning to turn a skeptical eye toward data centers in the state, particularly those used in crypto mining operations. Following testimony in June 2024 from the Chair of the Texas Public Utilities Commission and the CEO of the state’s energy grid (ERCOT), Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick (R) expressed concern about the strain data centers are putting on the state’s energy grid saying, “Crypto miners and data centers will be responsible for over 50% of the added [energy] growth. We need to take a close look at those two industries. They produce very few jobs compared to the incredible demands they place on our grid.”

While an onslaught of data center legislation is not expected nationwide, some states will likely be more active than others. For example, in Virginia, several pieces of legislation concerning data centers are scheduled for reintroduction in 2025. Senator Danica Roem (D) has three bills that are scheduled to be reintroduced in 2025 that would prohibit data center construction within one mile of a state or national park (VA SB 284 ), require data center developers to disclose their water and power demands (VA SB 285), and would require data centers to recycle stormwater onsite (VA SB 289). Other bills in Virginia that are scheduled for reintroduction in 2025 include bills to require data center operators to meet certain energy efficiency standards to be eligible for the state sales and use tax exemption on data center purchases (VA SB 192), allow localities to perform site assessment to determine the impact a data center will have on water usage and carbon emissions (VA HB 338), and require data centers to make quarterly energy source reports to the Virginia Department of Energy (VA HB 910). In other states, particularly those where data centers are a sign of potential promise instead of local concern, legislation that will impact data centers will most likely take the form of energy and water bills. Due to the extraordinary energy and water usage of data centers, states looking to attract data center development may look to pass legislation aimed at expanding their capacity for energy generation and transmission. States may also consider legislation aimed at water reuse or conservation that may have an impact on data center operations. Additionally, some of the remaining states that have yet to enact a data center tax exemption may consider doing so if they wish to compete with other states for data center development.

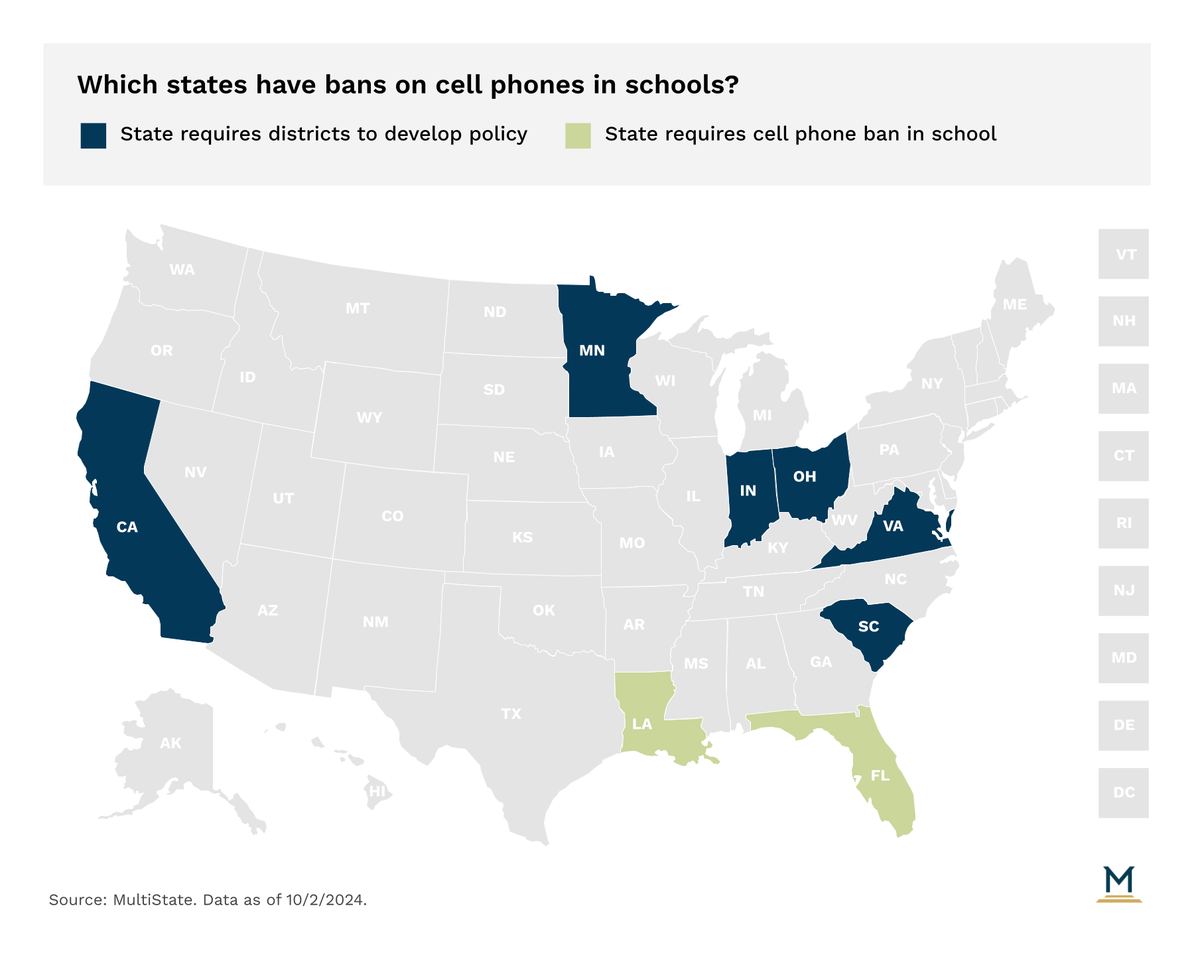

States and school districts around the country have identified the need to place limits on cell phones in schools and have started setting regulations around their use. Some school districts have put total bans in place, and others require students to lock phones away during instructional time. Parents believe that cell phones are a necessity for children due to safety and logistical concerns, but teachers and administrators believe that they create distractions and may contribute to other problems like mental health issues and bullying. The Surgeon General published a warning about social media use on youth mental health and urged policymakers to strengthen safety standards and limit access.

While some argue that cell phone bans should be regulated at the school district level, states are already starting to place state-wide bans on use in school, and states are addressing this in various ways. Virginia Governor Youngkin (R) issued an executive order to direct the Department of Education to establish cell phone free policies and procedures in Virginia schools. Louisiana enacted a bill in 2024 that prohibits their use at school. And in South Carolina, the budget contained a condition stipulating that school districts would not receive funding unless there was a cell phone ban in place.

Cell phone bans will continue to be a popular topic addressed by the states, whether at the school district level or in legislatures, in 2025. Legislators in New Jersey recently introduced a bill addressing student use of cell phones and social media platforms in schools and a bill has been drafted in Utah ahead of the 2025 session that prohibits cell phones and smart watches. As districts around the country begin implementing these bans in 2025 and beyond, there will surely be feedback from parents and teachers that will inform how other states move forward with this important issue.

MultiState’s team is actively identifying and tracking technology and privacy issues so that businesses and organizations have the information they need to navigate and effectively engage. If your organization would like to further track these or other related issues, please contact us.

April 8, 2025 | Liz Malm

-666769-400px.jpeg)

February 5, 2025 | Max Rieper

November 14, 2024 | Max Rieper